The Liverpool Biennial 2018:

or

Exhibitions People Who Like Sound Might Like

or

Sonic Arts Are Mainstream Now

or

Yes, sonic arts have been mainstream for a while but this is a music magazine so it’d make sense to cover it because we don’t really care so much for brittle postmodern ceramics as much as brittle postmodern noises

Hey, here’s a fun idea. Let’s compare, for a moment, the adverts you might see on public transport in London and Liverpool…

London: performances at West End theatres (£££), exhibitions at the V&A (£0 but for the affluent), plastic surgeons (£££££), job searches (well)

Liverpool: finish your GCSEs, charities hustling you for cash after you pop it, the Beatles.

Says a lot about a city, right? Now, last time I went to Berlin, the 2 adverts I saw most often (in Kreuzberg/Neukölln, obviously) were;

1. We’re-sick-of-your-lack-of-effort German language schools for hip Brits abroad.

2. Literally 3798204729 posters to study a Sound Studies and Sonic Arts Masters degree at Universität der Künste Berlin.

The lusty entanglement of digital media, music and and art has never been as zeitgeist as it is right now. Synths are no longer for hirsute hobbyists in damp basements; we all carry a personalised art gallery in our Instagram likes; an absurd amount of modern art writing and cultural criticism is habitually presented in txt speak.1I personally believe that a very serious percentage of sonic art can fall under the umbrella of digital art. Yes, yes, not all of it, but then again, it’s not your article, is it? Oh, and regarding text speak art/art crit, see here, here and here. The buoyant rise of institutions like AND Festival, Unsound Festival and the fact that FACT has cemented itself as the hangout du jour of the ‘Cool Art Clique’ (if my social feeds the day after the launch of States of Play 2 lol, can u tell I wrote this article a while back? are anything to go by)3If you went to a gallery opening but didn’t put it on Insta, you literally didn’t even go.*

*I don’t have the guts to put this flippant comment in the main body of the article, because whilst I truly despise the DoItForTheGram phenomena, a good 95% of people that I count as friends that go to gallery openings do exactly this and I don’t want them to feel attacked. The other 5% of people also do it but already just dislike them.**

**Actually, maybe I’m just neurotically over-aware of being millennial, yet not wanting to appear millennial. I’m just jealous others can so unselfconsciously ‘Gram away.***

***I actually worry about future self-erasure sometimes because I document my existence online so sparsely. In digital terms, which is to say, modern terms, I might as well not even exist, or, at any rate, never leave the house. then Sonic Arts Are In. Susan Philipsz was awarded the first ever Turner prize for an aural work in 2010. MoMA held its first sound art exhibition in 2013 and the 2015 Art Basel’s Unlimited focussed on sonic arts. It’s fair to say that sound art has hit the mainstream. It should be unsurprising then, that digital arts, music-centric exhibitions and sonic artists feature more heavily in this year’s Liverpool’s Biennial, and, they are the exhibitions that I, dear reader, look most forward to attending. Here’s a tour of the promising harvest;

*

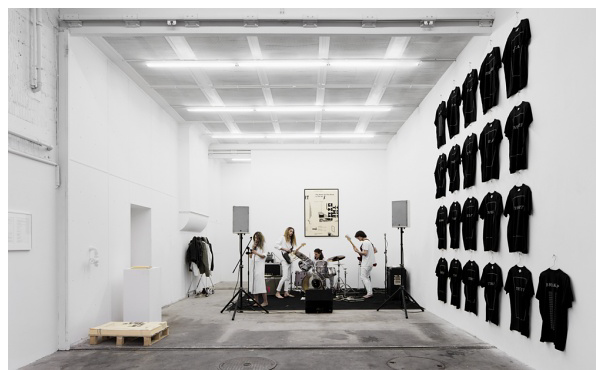

Ari Benjamin Meyers

Ari is a classical musician, composer, conductor and artists whose life in these twin circles often intersects. Some of his previous works Symphony 80 and Solo for Ayumi (both 2017) explore the process of musical composition and the interactions between producer and consumers. He’s collaborated with artists, bands and classical ensembles in the past, working with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Chicks on Speed and Tino Sehgal. For his foray into Liverpool, he’s going to be working alongside local musicians to create a series of film and performance portraits that will tell of Liverpool’s musical history. He’s interviewed local musicians - Bette Bright (Deaf School), Budgie (Siouxsie and the Banshees/Big in Japan), Ken Owen (Carcass) and Louisa Roach (She Drew The Gun) - about their personal connection to music, and has composed a bespoke solo piece for each musician to perform at the Playhouse. Each element of the work will be filmed and projected to the audience with varying degrees of overlap, forming a meta-narrative between each performer that reflects the nebulous, morphing state of Liverpool’s music scene.

The Biennial has come under fire in the past for a lack of cohesion with the local community and under-representation of local artists, so it’s nice to see commissioned pieces that are directly tied to the identity and history of the City. Frieze in particular hounded the early editions of the Biennial, accusing art as having been ‘co-opted as the most immediate signifier of newness’ in the context of Liverpool’s then burgeoning gentrification4I say ‘then’ with the utmost caution/complete offhand disregard. The current gentrification of Liverpool is an entirely different beast, I think, to what it was then, and is entirely beyond the scope of this article. Go check Bido’s Liverpool Music City https://bidolito.co.uk/liverpool-music-city/ or State of the Arts boss article here http://www.thestateofthearts.co.uk/features/tale-two-ten-streets-liverpools-regeneration-gentrification/ Or Seven Streets bracing, totally deserved, shit-throwing http://www.sevenstreets.com/liverpool-forgotten-independents-heritage which leant heavily on imported cultural capital, rather than spotlighting the talent and dynamism already present in the city. ‘If contemporary art is to matter to Liverpool’ said Frieze, ‘it must have something to say about the city.’5It’s easy to dismiss London-centric, hawk-nosed publications such as Frieze or Apollo as peacocking in their ivory towers down in our revered, foreign Capital, yet ultimately their opinions do matter. Liverpool publications throughout the years have reliably churned out press releases trussed up as reviews, drenched in obsequious, greasy praise. Yet, international, respectable press condemns us as provincial and dull. It seems that Liverpool Biennial has taken note.

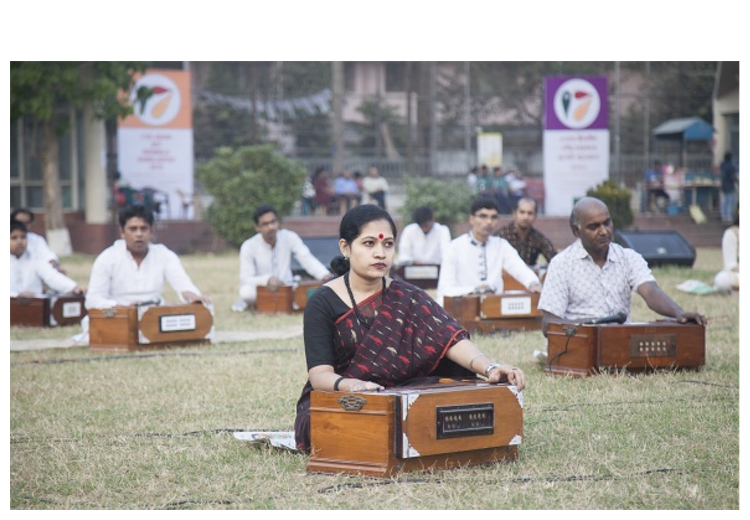

Reetu Sattar

Reetu’s work for the Biennial, Harano Sur (Lost Tune), manifests itself in a filmed performance. Her practice has historically explored cultural memory, loss and the ephemerality of existence. Here, Harano Sur posits that cultural identity and musical heritage are inextricably intertwined, and that erasure of the latter is by default erasure of the former. Commissioned by the Dhaka Art Summit, Harano Sur draws together 29 musicians each of whom play a single note of the heptatonic harmonium. Ingrained in traditional Bangladeshi music, the harmonium is undergoing a disappearance due to increasingly strict interpretations of Islam in Bangladeshi communities, and is in danger of being maneuvered out of the modern musical landscape. Using drone, sustention and elongation, the singular notes in unison become a statement on diasporas and resilience.

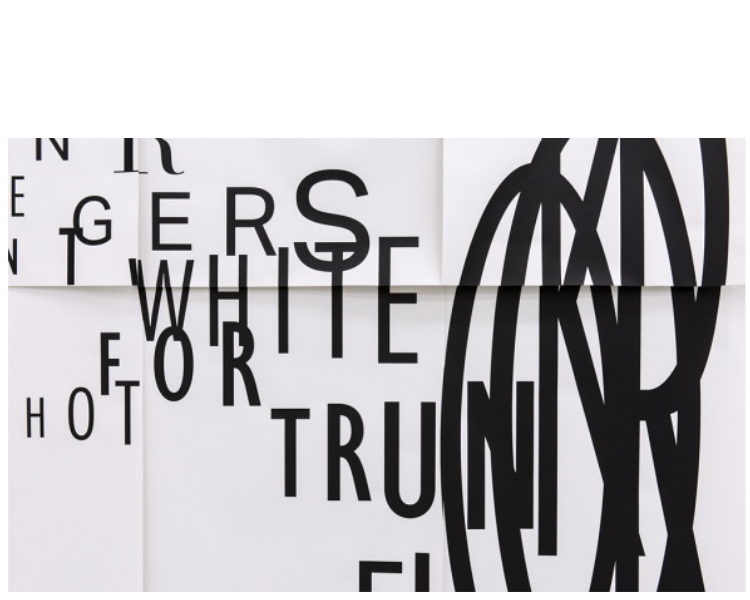

Janice Kerbel

Janice Kerbel is the Turner Prize nominated artist accused of ‘disrespecting musc’ for her performative piece DOUG, a nine-part song cycle, in 2015. I recently heard, on good authority, that it is ‘impossible’ to perform. Her works have taken the form of audio recordings, radio play, operatic compositions focussing on communication, miscommunication and the nature of accident. DOUG, a performative piece that told the adventures of the eponymous Doug’s misfortunes, was composed for professional singers with all the prerequisite accoutrements of contemporary composition, but was specifically housed in art galleries rather than concert halls. The work sharply divided critics, with some seeing her work as bad music disguised under the auspice of Art (with a capital A, no doubt,) whilst others see her practice as exploring the modern preoccupation with the contextualisation (and subsequent class distinction) of cultural objects. With her work for the Biennial currently kept hush-hush, we’re curious to see what Kerbel has in store.

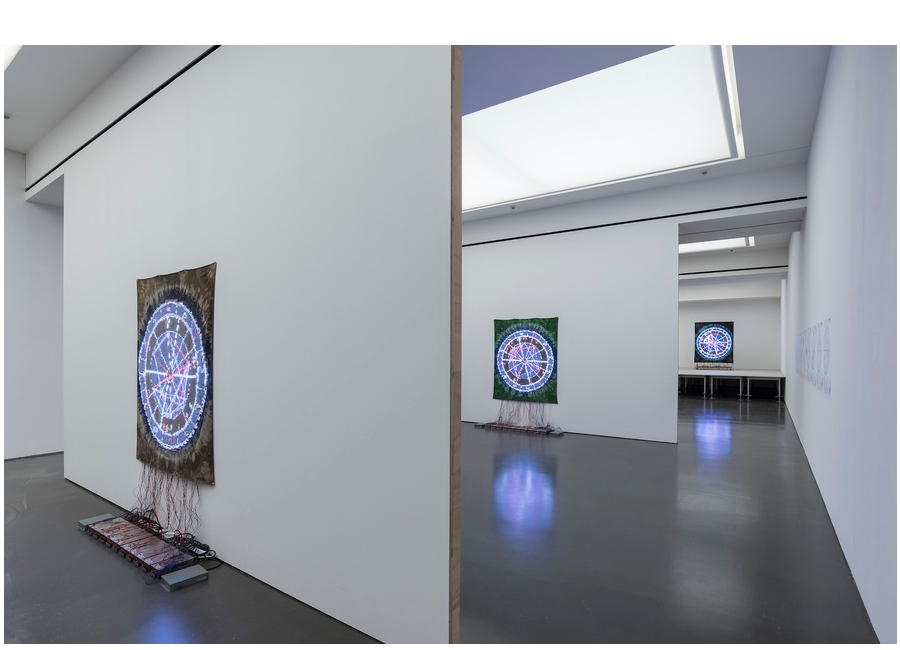

Ei Arakawa

Ei Arakawa in a Japanese-born, US-based artist whose practice combines choreography, spontaneous action and installation. Flipping normal notions of authorship and ‘The Artist’ on their head, Ei explores the relationship between audience and performer, and heavily collaborates with other artists to produce his own works, destroying the selfhood of his artistic identity. His ‘paintings’ are composed of LED light panels and amplified digital sounds, each a canvas crooning a song about itself. In Harsh Citation, Harsh Pastoral, Harsh Münster (2017), his paintings displayed animations of paintings by the likes of Joan Mitchell and Amy Sillman. For the Biennial, Ei will create a new LED painting in association with Silke Otto-Knapp, another Biennial artist, as well as a new sound show to accompany the piece.

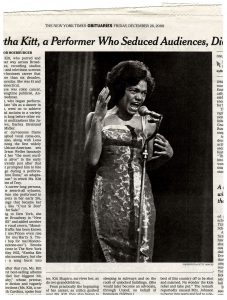

Joseph Grigely

One for the fans of pop music history and celebrity culture, Joseph Grigely’s addition to the Biennial lineup showcases elements of his Songs without Words series. Providing a sort of visual analogue remix, he’s taken iconic newspaper images of musicians and removed the accompanying captions in order to provoke discussion of the significance of context and the ambiguity of sound when curatorial direction is removed.

Morehshin Allahyari

Morehshin Allahyari perfectly embodies the intersection between modern digital processes and fine art. Her work She Who Sees The Unknown (2017), housed in the Photographer’s Gallery in London last summer, explored modern data colonialism and digital xenofeminism through depictions of dark goddess and feminine monsters of myth through 3D scans of (re)appropriated artefacts. Within the wider narrative of the artistic practices emerging and being showcased by the next generation of artists in the city - here, I’m thinking FACT’s successfully fostering of digital exhibitions, and ongoing dedication to sonic and multimedia arts,6Everyone who gives a h00t or two about sonic arts should have attended FACT’s 15th birthday celebrations with Robin Fox (DJ\A/V) and Aurora Halal (techno witch/video artist). and the Royal Standard’s often politically-fired output, Morehsin makes complete sense as an addition to the Biennial roster. For this Biennial, Morehshin will showcase a new online commission.

*

The Biennial’s latest crop of artists working with sound have some pretty big boots to fill, with previous years bringing some remarkable pieces into the public gaze. Beirut-based artists, Lawrence Abu Hamdan appeared on the roster for Liverpool’s 2016 Biennial. His practice often explores themes of social surveillance, political control, human rights violations and border control through their manifestations in sound. Outside of his artistic practises, he makes audio analysis for legal investigations and advocacy. His video Rubber Coated Steel visualised the audio-ballistic analysis of recorded gunshots following the death of two teenagers, Nadeem Nawara and Mohamad Abu Daher, in the occupied West Bank of Palestine in 2014. The audio-forensics determined whether the soldiers had used rubber bullets, as they claimed, or broken the law by firing live rounds at two unarmed teenagers. The Hummingbird Clock displayed outside the courts on Derby Square reappropriated the government technique of recording the sounds of the electrical grid in order to timestamp and geolocate CCTV footage, a technique that has been in use for over a decade. The Hummingbird Clock was the first time this method of surveillance was made use of outside of the state, creating a public sculpture that also freely gave open data. In the intervening years, Lawrence has gone on to create a new work for the Sharjah Biennial, focusing on the audio memories of survivors of Saydnaya prison in Syria, an incarceration camp that uses almost complete sensory deprivation, silence and isolation.

It has been pretty pleasing to see that the last few iterations of the Biennial have become increasingly politically motivated, which is why Reetu Sattar and Morehshin Allahyari’s appointment feels fresh and relevant, rather than allowing the sonic and digital art exhibited in Liverpool to rely on overcooked rehashings of The Beatles.7C.f. Cildo Meireles at Liverpool Biennial 2004, omg eyeroll. This year in particular takes a distinctly anti-Eurocentric approach, deliberately facing outwards and into the face of the social, political and economic turmoil that 2017/18 has brought. As such, their lineup aims to reflect on a more global stance, with more than 40 international artists from 22 countries gathered under the title Beautiful World, Where Are You? With the under-representation of people of colour and diverse genders finally hitting mainstream discussion, the Biennial are doing their part to attempt a lineup that doesn’t just orbit around white European men. And all power to them for it.